A Strip of Fabric

Fashion Victimhood, Art Imperialism, and the Gaza Strip | My Candid Return to Substack

Sartorial rules are simple: Do not wear white after Labor Day, never wear business casual to the club, and most importantly, never become a fashion victim.

The term fashion victim, as coined by Oscar de la Renta, is used to identify one who gets caught up in the excess of fashion, whether they are fad followers or hyper-materialists or that secret third thing… me.

Though I do not monetarily invest in fashion in the way one would define a fashion victim, I do frequently find myself cashing in the entirety of one of my most valuable assets — my time. Fashion victimhood has always been used to identify someone who engages with fashion on a consumerist level, but I view temporal investment as capital that holds equal value to tangible wealth and frankly, for the better part of this year, I have wagered the full extent of my time getting caught up in this ambiguously defined excess of fashion.

What they don’t tell you about fashion victimhood is that it is an inevitability. To make an intentional effort in not being a fashion victim, is to be a fashion victim. Even if I were to subvert materialism and faddishness by adhering strictly to a minimalistic antifashion wardrobe, I’m still trying to chicly signal to a different subculture that I am a part of their more educated and more worldly group; all while ignorantly overlooking the fact that I continue to be controlled by fashion victimhood by completely altering my taste to fit the more enlightened mode du jour.

Getting caught up in the excess of fashion is also an inevitability to everyone who tries to subvert it. Not necessarily in terms of materialistic overconsumption, but rather in the intemperance of information — this is where my fashion victimhood resides.

Anyone who knows me well knows that I have an opinion on everything that has happened since the beginning of time. Ask me about my opinions on quantum cosmology or Scandoval, I will answer both with equal diligence. Anyone who knows me vaguely knows that I seemingly hate everything that has ever happened in fashion. Both are true to different extents.

If you follow me on Twitter1, you might have noticed or possibly even wondered why my bio is “loves fashion, hates Fashion.” I’ve always told myself that I wanted to go into fashion purely for the love of it. Even the hatred I hold towards the capital-F fashion industry comes from a place of love and longing to make it a safer and more equitable place. But the reality of it is, it’s not, nowhere close, not even a little, and I have opinions on it all, thereby contributing to the excess of fashion in my attempt to resist it.

I’ll be the first to admit that I started this Substack incredibly overzealous. I had plans to post thoughtful essays 3 to 4 times a week and I still have lists in my notes app of hundreds of topics I would like to write about, but I quickly learned that the rate in which the fashion industry exploits vulnerable populations is much faster than my ability to appropriately and thoroughly address them with the attention that the industry deprives them of.

I first started to lose momentum for writing during the antecedent events of the Met Gala. The HFTMG team and I were the first to publicly condemn the theme celebrating the legacy of Karl Lagerfeld. We were quickly met with a sea of backlash spanning everyone from internet trolls to established industry professionals for our attempts to “erase fashion history.” However I rather ignore history entirely than celebrate a rewritten one.

My team was never even calling for the erasure of Lagerfeld’s contribution to fashion history, but rather asking for a transparent exhibit that included the dangerous rhetoric he spread during his 50-year career.

Art is anthropology, to try and disingenuously portray the ideology that shapes it devalues it of any meaning. If I wanted to just look at clothes I would go to Saks Fifth Avenue, but museums have the moral responsibility to teach the public of how said clothes are contextualized within a sociological landscape — that was my argument from the beginning.

Watching the work that the HFTMG team and I did quickly get buried by the celebrity fanfare was incredibly disheartening. I don’t want this to come across with a semblance of narcissism because this work was never about us as individuals. It was about us being members of every disenfranchised group that Karl Lagerfeld directly targeted: queer people, Muslims, plus-sized individuals, people of color, women, survivors of sexual assault. It was about us discovering that Numéro Magazine allegedly deleted any remanence of Lagerfeld’s interview defending Karl Templer by telling his victims “If you don't want your pants pulled about, don't become a model! Join a nunnery,” a mere few days before the Met Gala’s theme was announced to the public. It was about the most prestigious institutions in fashion knowing all of this, actively concealing it, and then watching every single person who had no other choice than to remember it be accused of erasing history.

It was about systemically becoming a fashion victim.

My fashion nihilism culminated last month when Sean McGirr replaced Sarah Burton as creative director of Alexander McQueen, in turn, making 100% of Kering’s creative directors white men. Later through researching the statistics of other fashion conglomerates, I learned that this statistic should’ve surprised no one and frankly I felt stupid for expecting any different outcome. My findings were as followed:

LVMH:

22% of creative directors are white women

16% of creative directors are men of color

0% of creative directors are women of color

Kering:

0% of creative directors are women and/or designers of color2

Puig3:

20% of creative directors are white women4

0% of creative directors are designers of color

Richemont:

0% of creative directors are women and/or designers of color5

But again, after posting these statistics on Twitter, I was met with backlash. People condescendingly asked me “why can’t you just focus on good designs?” and again my response was, art is anthropology. If you can overlook the fact that the overwhelming majority of creative directors are favorable within the eyes of patriarchy and white supremacy, I can draw the conclusion that you overlooked the fact that for centuries these same systems of oppression have defined what qualifies as artistic goodness.

As a woman in the arts and an intersectional ally to all fashion victims, when I see these statistics I am physically incapable of “focusing on good designs.” I’m far too busy thinking about Guerrilla Girls' posters that read “Less than 5% of the artists in the Met’s modern art section are women, but 85% of the nude paintings are female.” I’m far too busy thinking about how Linda Nochlin’s Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?, the essay that radicalized me as a preteen, was bastardized into a graphic t-shirt by Dior only for its sales to line the pockets of their brand ambassador who was convicted of 12 counts of domestic abuse. I am far too busy thinking about the communities of Accra, Ghana and Panipat, India who have designer clothing clogging their water supply, since they are victims of the colonial practice of garment dumping because, by no mistake, the fashion industry has ruled that the West’s excess of fashion is more valuable than the quality of life in the Global South.

And nowadays I am far too busy thinking about how less than five years ago, every major fashion company was having a pissing contest over who could donate the most money to restore Notre-Dame, all in the name of “preserving art history,” but now, not only are many of these same brands complicit in the genocide of Palestinian artisans and the cultural erasure of Palestinian art, several are actively funding it.

Refusing to view art as anthropology and ignoring the hands that either created or destroyed it makes you complicit in art imperialism. Refusing to critically analyze the history of artistic goodness makes you a cosigner in deciding which cultural arts are worthy of preserving and, by extension, which cultures are worthy of living.

Over this past month, I have been trying to learn as much as possible about Palestinian fashion and its artisans. I feel like that is where I can contribute and communicate best considering my given skill set and platform. And seeing that many fashion writers have been threatened by their employers for speaking out about Palestine, I figured, might as well talk about what we are all allowed to talk about: fashion. Because what are you going to do? Accuse us of erasing fashion history? Accuse us of not focusing on the right good designs? Blacklist us from an industry that never made space for us in the first place? You have given us power in having nothing left to lose.

Like I said in the beginning, time is capital that holds equal value to tangible wealth. But while the Western fashion industry has been basking in their excess of fashion, they have simultaneously made time a limited resource in the Gaza Strip. Using the fashion industry’s own capitalist praxis, scarcity drives demand, so there is no more apt time than now for us to talk about Palestine.

So let’s talk about Palestine.

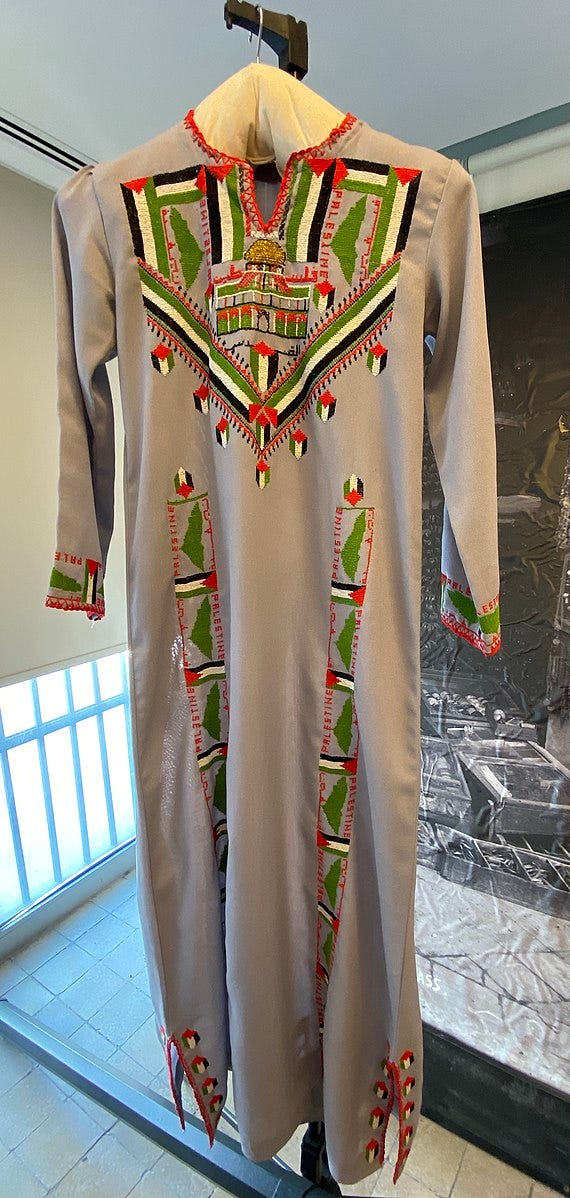

Palestinians have sartorial rules of their own. Found stitched into their thobes, the form of cross-stitching known as tatreez was not born out of faddishness or materialism, but rather necessity. This ancient craft, primarily practiced by Palestinian women, serves as a multifunctional visual history of Palestine and a reminder that each and every wearer has a unique identity and ancestry worth preserving.

Tatreez is heritage. Each city in Palestine has their own unique symbols and color schemes that represent where they hail from. The cypress trees found on Gazan thobes represent the plants that border the agricultural fields in Gaza that functionally serve as windbreakers, while cities further inland such as Hebron and Ramallah have threads of deep purple and red as they are dyed in the climates where pomegranates are in abundance.

Tatreez is adaptation. It evolves in response to the social climate of its wearers. During the first Intifada (1987-1993), after a series of Palestinian uprisings broke out in response to the occupation, the Israeli government banned all displays of the Palestinian flag. As stated in Military Order 101: Article 5, "It is forbidden to hoist, wave or place political flags or symbols, except by permit of the military commander." But since the colors of the flag themselves were not banned, Palestinians used the art of tatreez to incorporate the country’s colors into their clothing. Creating what is known as the intifada thobe, tatreez artisans wove red, white, black, and green threads into thobes alongside maps, olive trees, oranges, and other innocuous symbols synonymous with Palestinian culture.

Overtime, as the definition of “symbols” became more strict, Palestinians adapted by creating new ones that covertly displayed allegiance to their homeland; one of the most recognizable symbols being that of a watermelon. The green and white rind, red flesh, and black seeds were a discrete display of Palestinian colors that quickly became a reoccurring theme that marked the literal and metaphoric social fabric of Palestine.

Tatreez is perseverance. Even after the 1948 Nakba, where 531 Palestinian villages were leveled and buried, 15,000 Palestinians were murdered, and 700,000 Palestinians were placed into exile, this art form sustained. From inside the walls of refugee camps in Jordan and Lebanon, Palestinian women have built thriving art collectives teaching a new generation of artisans how to keep this craft alive. These art collectives have enabled Palestinian women to provide for their families and to rebuild.

In a way, Palestinians have a sort of symbiotic relationship with their cultural dress. They stand just as much a symbol of it as it does a symbol of them: heritage, adaptation, perseverance.

because Palestinian art is anthropology.

American cultural institutions might have the ability to rewrite history or ignore unfashionable legacies, but the rest of the world does not have the luxury of existing within a vacuum. The rest of the world is clinging onto an ever-dwindling representation of their humanity as it gets buried in the West’s excess of fashion.

Ignorance is not bliss, it is privilege.

So, yeah, sartorial rules are simple: wearing white after Labor Day or business casual to the club makes you just as much a fashion victim as the person who rejects both on the simple premise that an arbitrary system of authority told them to do so. It’s also no coincidence that these fashion faux pas have roots in classism and white supremacy; you are inevitably and systemically made a fashion victim before you even have the chance to get dressed. It no longer matters what you wear, so long as you wear it on the right side of history — the same side of history you’ll be accused of erasing.

Disclaimer:

I do not condone antisemitism in any way, shape, or form. It is my own relationship with antisemitism and being the granddaughter of a first-generation American Jew whose parents were holocaust-surviving refugees that shape my opinions on Zionism.

My firm stance on Zionism is that it is an axis of the same Western imperialism that created the Holocaust. Western nations have militarized the same Jewish grief they inflicted and capitalized on the abundant antisemitism in their own nations in order to colonize Palestine.

Zionism is not exclusively a Jewish ideology. In fact, Jewish people do not even make up the majority of Zionists. The largest Zionist organization in the United States is Christians United for Israel; their membership extends 10 million in the one organization alone. There are only 7.5 million American Jews in existence. According to geopolitical expert and Queen’s University Belfast professor, Tristan Sturm, there are over 30 million evangelical Zionists in the United States. The global Jewish population is 16 million. That is almost two American evangelical Zionists for every single Jewish person alive, Zionist or not.

It’s incredibly frustrating to watch these historically antisemitic governments and corporations fund other governments and corporations in the name of helping “the Jewish cause” when antisemitic hate crimes are at an all time high in their own backyard.

There’s a reason why the United States Federal Government pays for the healthcare and extended education of American Jews who relocate to Israel, but does nothing to financially assist the 1/3 of all Holocaust survivors who live below the poverty line in the U.S.. When you disenfranchise people for generations and financially incentivize them to leave, they will have no other choice than to leave.

The West’s unwavering support for Zionism isn’t out of love or even guilt, but rather in attempt to dissolve the Jewish diaspora, kill or displace the indigenous population of Palestine, capitalize on for-profit American missile companies, and place all blame back on the Jewish people.

When I say Zionism, I am and always will be using it synonymously with Western imperialism. And when I call myself an anti-Zionist, it is and always will be because I refuse to recognize it as a Jewish cause.

References:

Embroidering Resistance: Palestinian Tatreez by Ruofei Shang (Atmos)

Heart, Mind & Spirit: Some Advice on Choosing a Color Palette by Wafa Ghnaim (Tatreez & Tea)

The Secret World of Tatreez: From Orange Blossoms to the Nakba by Pink Jinn

Tatreez and Development by Saniah Naim (Anera)

Tatreez & Tea’s Tatreez Introductory Model and Masterclass Series by Wafa Ghnaim (Truly one of the most thorough folk art databases I’ve ever seen, Wafa Ghnaim is incredible.)

This Is Artful Resistance: The Power of Tatreez by Erin Quinn (SOAS University of London: Gender Studies)

Woven Legacy, Woven Language by Jane Waldron Grutz (Saudi Aramco World)

Seminal Works on Palestine:

The Battle for Justice in Palestine by Ali Abunimah

Captive Revolution: Palestinian Women’s Anti-Colonial Struggle Within the Israeli Prison System by Nahla Abdo-Zubi

Freedom Is A Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the Foundations of a Movement by Angela Y. Davis

The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance by Rashid Khalidi

The Politics of Dispossession: The Struggle for Palestinian Self-Determination by Edward Said

Queer Palestine and the Empire of Critique by Sa’ed Atshan

The Question of Palestine by Edward Said

Anti-Zionism by Jewish Authors:

Beyond Chutzpah: On the Misuse of Anti-Semitism and the Abuse of History by Norman G. Finkelstein

The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine by Ilan Pappé

Except for Palestine: The Limits of Progressive Politics by Marc Lamont Hill and Mitchell Plitnick

Gaza in Crisis: Reflecting on Israel’s War Crimes Against the Palestinians by Noam Chomsky and Ilan Pappé

On Palestine by Noam Chomsky and Ilan Pappé

For further reading, visit Decolonize Palestine’s Complete Reading List.

I will continue to refer to “X” as Twitter, I refuse to bow to Elon Musk

June Ambrose is the creative director of Puma, but Kering recently dropped their stake in Puma from 86% to 5.9% and is no longer the majority shareholder

Puig has one gender fluid creative director: Harris Reed at Nina Ricci

Florence Tétier is the creative director of Jean Paul Gaultier though she has not produced a runway collection since Gaultier’s retirement

Gabriela Hearst’s spot at Chloé still remains unfilled

Gosh Chloe this one is incredible. Thank you so much for doing the research and writing about tatreez and weaving such a cohesive narrative between white supremacy and Zionism. I’ve been so heartened to see the sustainable fashion influencers/writers that I follow (Aja Barber comes to mind) use what they know to shed light on Palestine. It’s clear that the framework of injustice in fashion is so easily applicable to Palestine. Thank you for this!

This one right here 👆🏽🔥 thank you so much for doing what you do. I know burnout is very real for those of us doing the work. I really appreciate reading your posts!