To start off this series of runway analyses, it’s only right to begin with my personal favorite show, Alexander McQueen’s 2001 Spring/Summer collection, Voss.

To understand the importance of this show, we have to discuss the history of Lee McQueen and what led up to this point. Voss took place during an incredibly pivotal era of McQueen’s life and career. At the time, he was departing from his position as chief designer at Givenchy. Both he and the company had polarizing views on the boundaries of fashion. Historically Givenchy kept a very classic and timeless brand image popularized by the likes of Audrey Hepburn, Suzy Parker, and Dorian Leigh.

McQueen, however, liked to test the limits of Givenchy’s identity. Most famously during the 1997 Autumn/Winter Couture collection, Eclect Dissect, where he made an exact replica of Hubert de Givenchy’s gown for Audrey Hepburn in My Fair Lady. While this was initially thought to be the closing bridal gown, it was only the collection’s penultimate look. To close the show, Jodie Kidd walked down the runway in the exact same dress in black, adorned with an important motif of McQueen’s, taxidermy birds.

At the time, changing the traditional bridal look at a couture show was incredibly taboo. Hubert de Givenchy himself described McQueen’s era at the brand as “a total disaster.”

McQueen started his namesake label, Alexander McQueen, in 1992 which allowed him an outlet for the creative expression that was limited during his tenure. During his last few contentious seasons at Givenchy, Lee McQueen went from working as head designer for a major fashion brand with a large atelier, to spending most of his time designing alone. This solitude took a toll on both his mental and physical health. With all eyes on him now designing under his own name, he felt pressured into drastically changing his appearance.

After losing a significant amount of weight and various cosmetic procedures, McQueen expressed that he was no longer a person he recognized. He compromised his health, appearance, and well-being for the industry that ridiculed him. All of this pain and anger is what led to the birth of Voss.

Voss is comprised of two main themes, mental suffering and nature, more specifically, the beauty of nature when it is left untouched. The collection’s title “Voss” comes from the name of a Norwegian town known for its natural scenery and wildlife— both of which can be seen within the designs of this collection.

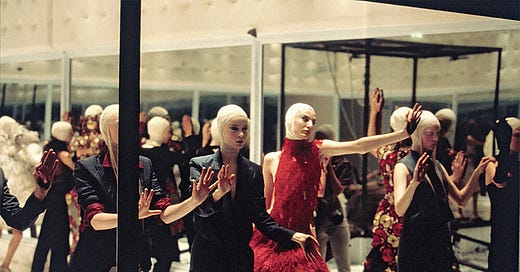

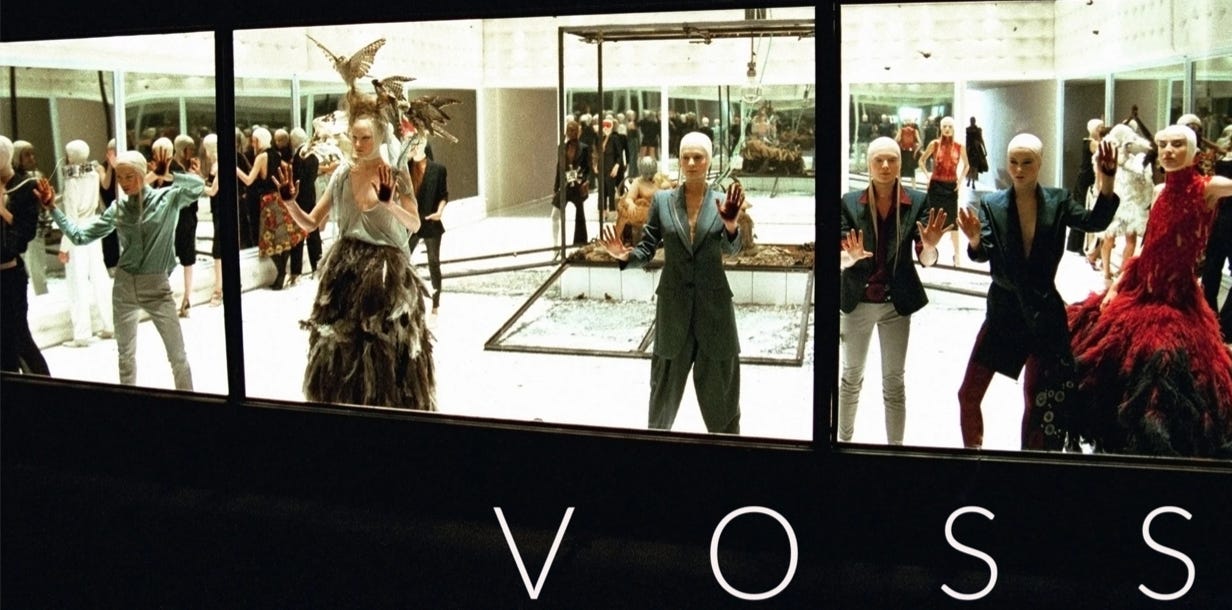

The runway for Voss took place inside of a box with padded walls and was enclosed by a two-way mirror on all sides. While this set is commonly understood to resemble a psychiatric hospital, one alternative perspective comes from Frank Darabont’s film The Green Mile (1999), which tells the story of inmates living on death row, adding an additional layer of confinement and nihilism to the show.

The audience’s chairs faced towards the box on all directions. Prior to the show, with the house lights on, the guests could not see beyond the glass. The attendees were forced to sit and face their reflections for nearly an hour. McQueen sat in the wings and watched as the crowd became visibly uncomfortable through a monitor. He stated that this stunt “was a great thing to do in the fashion industry — turn it back on them.”

When the show finally started, the two-way mirror switched. Allowing the audience to see into the box, but the models could not see out. This detail of the show is two-fold. The more obvious side being the set before the show began, forcing the audience to experience the voyeuristic torture that they put McQueen through, but the inability to see outside the box serves a unique perspective of its own. The models wearing McQueen’s designs — an extension of the designer himself — are stripped of their visibility. This illustrates McQueen’s beliefs of existing only for the industry while receiving nothing from them in return.

Kate Moss opened the show in a sandy-colored gown swathed in feathered chiffon. The model meandered around the box, pressing up against the glass, displaying a sense of agitation to add to the claustrophobic feel of the set. Moss was one of the many models whose head was wrapped in medical bandages, resembling that of a lobotomy patient.

This stylistic choice is often assumed to be a nod to Baron de Meyer’s 1927 editorial for Elizabeth Arden. De Meyer became the first official fashion photographer for Vogue and Vanity Fair in 1913, but he abruptly ended his position to work for Condé Nast’s rival Harper’s Bazaar. Evidently this sudden career shift parallels that of McQueen’s, both of whom left established fashion conglomerates to work for a rival company that allotted more creative liberty.

McQueen’s reoccurring taxidermy bird motif made its way onto Look 24, modeled by Jade Parfitt. The ensemble consisted of a floor-length skirt made of bird feathers and a headdress adorned by three stuffed hawks. The birds appear to be ripping the models blouse and bandages while the skirt remains untouched. This is another example of McQueen “turning it back” on the industry. Only the elements of the look that are manmade are being destroyed, while the natural remains unscathed. This directly opposes the pressure McQueen faced from his contemporaries to change his natural appearance and turn to cosmetic surgery.

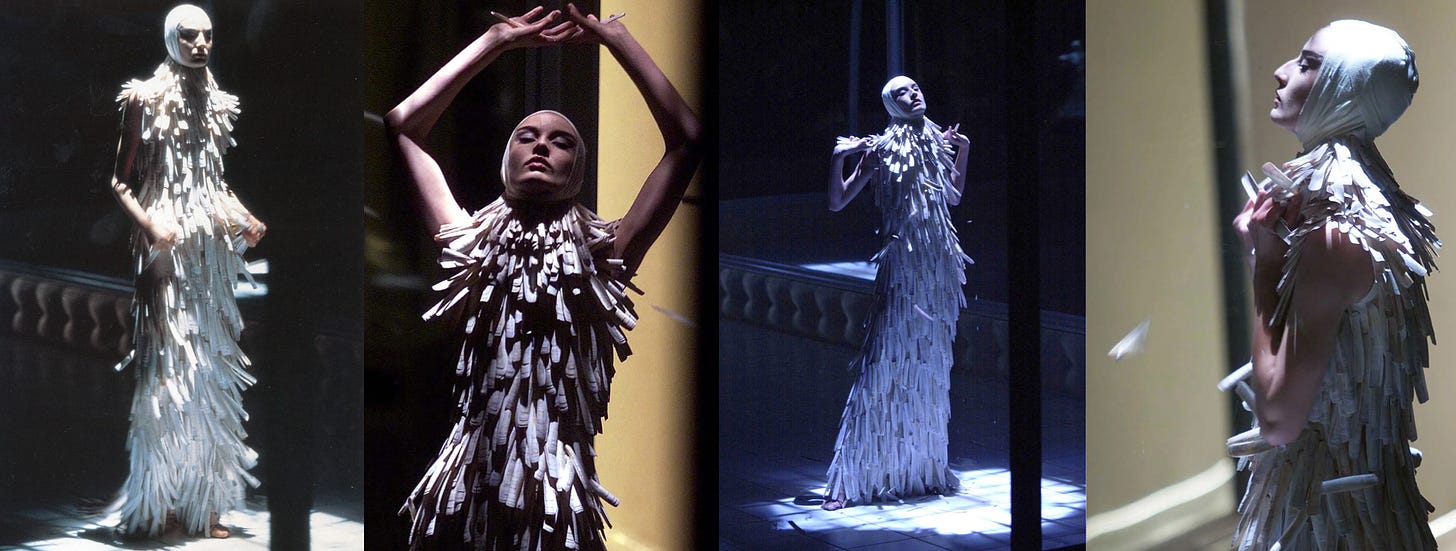

Look 33 is perhaps the perfect antithesis to Look 24. Erin O’Connor is seen wearing a dress made entirely of razor clamshells. McQueen instructed O’Connor to step onto the runway and immediately start ripping the shells from her dress. Consequently O’Connor sustained injuries during this performance with the serrated edges of the shells leaving cuts across her hands. This entire performance was one of the most memorable parts of the collection as well as the most blatant display of the mistreatment McQueen endured — a person being forced to strip themself of the very thing they are made of for no other reason than being instructed to do so.

Going along with the setting of a mental ward, McQueen drew inspiration from recreational room activities commonly found in psychiatric hospitals. Various ensembles are seen adorned with accessories made of puzzles of Bavarian castles and decks of cards. This unique repurposing of common room games can speak to the length of time the models, and McQueen himself, have been left in this captivity. Gradually their intended function becomes a bore, so to occupy their time they quite literally had to fashion the games into something new.

In addition to Norway, Voss was also heavily inspired by elements of Japanese design. Look 65, modeled by Karen Elson, consists of a dress made from a repurposed antique Japanese silk screen sourced by McQueen himself. The intricate embroidery of flowers and birds were carefully removed from the silk panels and transferred to the dress without being reshaped in any way. The original craftsmanship of the embroidery was preserved thus serving as another example of the conservation of beauty.

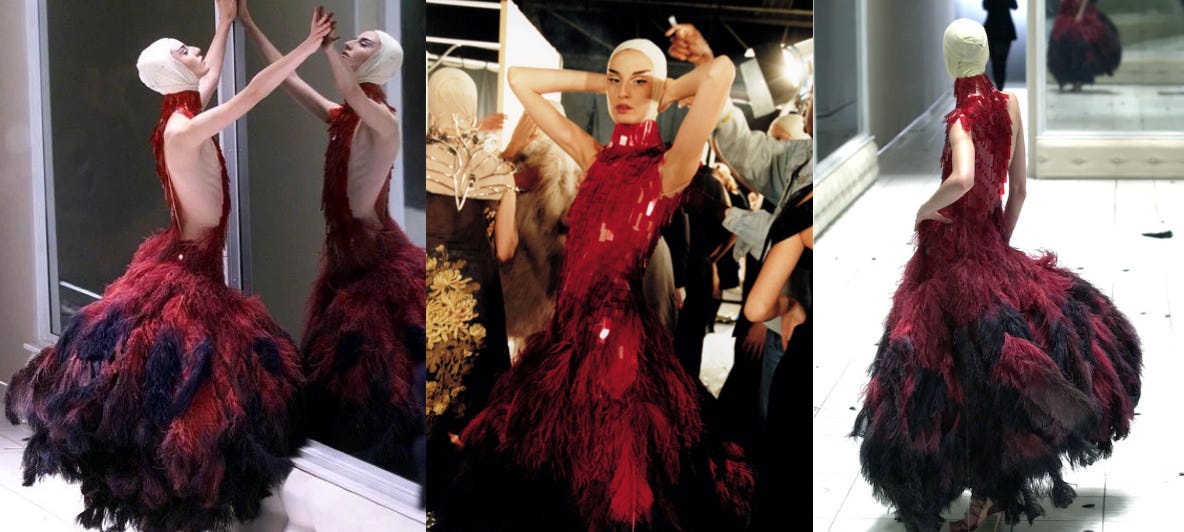

Erin O’Connor returned to the runway for the closing look of the collection. The design consisted of a skirt made from ostrich feathers dyed red and black and a bodice made from hand painted microscope slides. These slides were used to represent blood and the inside of the human body; one final design to tie in the theme of the natural state of beauty.

As the models exited the runway, the sound of a beating heart played throughout the venue. As the heartbeat flatlined, a box in the center of the glass encasement shattered. Live moths rushed out of the box, revealing Michelle Olley, a writer and plus-sized model, as the centerpiece of the runway. Olley, laying elegantly on her side wearing a winged mask connected to a breathing apparatus, displayed a live recreation of Joel-Peter Witkin’s photograph Sanitarium (1983). This performance, both eerie and graceful, concluded Voss and left the audience with a final question:

What is the true nature of beauty?

i am so happy i subscribed to your substack, this is beautiful, thank you.